Since 1968, Ian Macdonald has consistently photographed the people and places of Teesside, one of Europe’s most heavily industrialised area in the Northeast of England. His love of the region, the beauty of the landscape – great expanses of wildness nestling among industrial settings - and his solid admiration for the people working and living amongst this environment has resulted in a completely honest and passionate depiction of a place and its community.

In celebration of five decades of extraordinary work by the esteemed British artist and photographer, Sunderland hosted a major retrospective exhibition, Fixing Time. This exhibition spanned two venues: Sunderland Museum & Winter Gardens and the Northern Gallery for Contemporary Art.

Ship Number 1360 on the building berth in the early hours of launch day at the Smith’s Dock shipyard, South Bank, near Middlesbrough, 1986.

Your retrospective exhibition, Fixing Time, has opened this year in Sunderland, showcasing 50 years of your work across two venues. While your photography has been exhibited throughout the UK before, this comprehensive exhibition is being held in the North-East of England, where the majority of your photographs were taken as well.

What does it mean to you, personally, to have your work exhibited in the very region where you captured these images, and what is it like to present your work to the local community and to the people you’ve documented over the years?

Many of us are comfortable in the region we come from. In my case most of my drive comes from my early years spent on Teesside thirty or so miles south of Sunderland. Sunderland is on the estuary of the river Weir, which is very different to the river Tees. What we do have in common, beside lovely sandy beaches and the freezing cold North Sea to swim in, is shipbuilding. So having the opportunity to present two exhibitions, each particular in their own way, is such a rewarding way to work through my archive and go back in time to try and fix my own sense of history. Already the response is very rewarding not only in a certain admiring way, photographically as it were, but also, and more importantly to me a way of people identifying with what the pictures have to say.

Striking Block in the Riggers loft

Picnic on Bran Sand, South Gare, Teesmouth, c. 1982

The exhibition at the NGCA is titled Fixing Time, an aim that you mentioned in a previous interview stems from your desire to halt or display the passage of time by capturing it, making it permanent through your photography.

Could you elaborate on why this aim is important to you? What drives your commitment to preserving these moments and subjects?

I believe my artistic life is spent trying to answer this question. Where does this drive, this desire, this almost obsession come from. I love certain aspects of history as much as I love music, poetry, the novel… things which inspire me and I think it stems from a desire to make certain feelings permanent… or as permanent as possible given the very fragility of much of what goes on around us. I seem to identify with a variety of things which in there turn form the basis of what I try to say through drawing and through the photographs I make.

Billy Rowland’s houseboat following the fire, 1977

Cold weather clothing in the Rigger’s loft, Smith’s Dock shipyard, South Bank Teesside, 1987

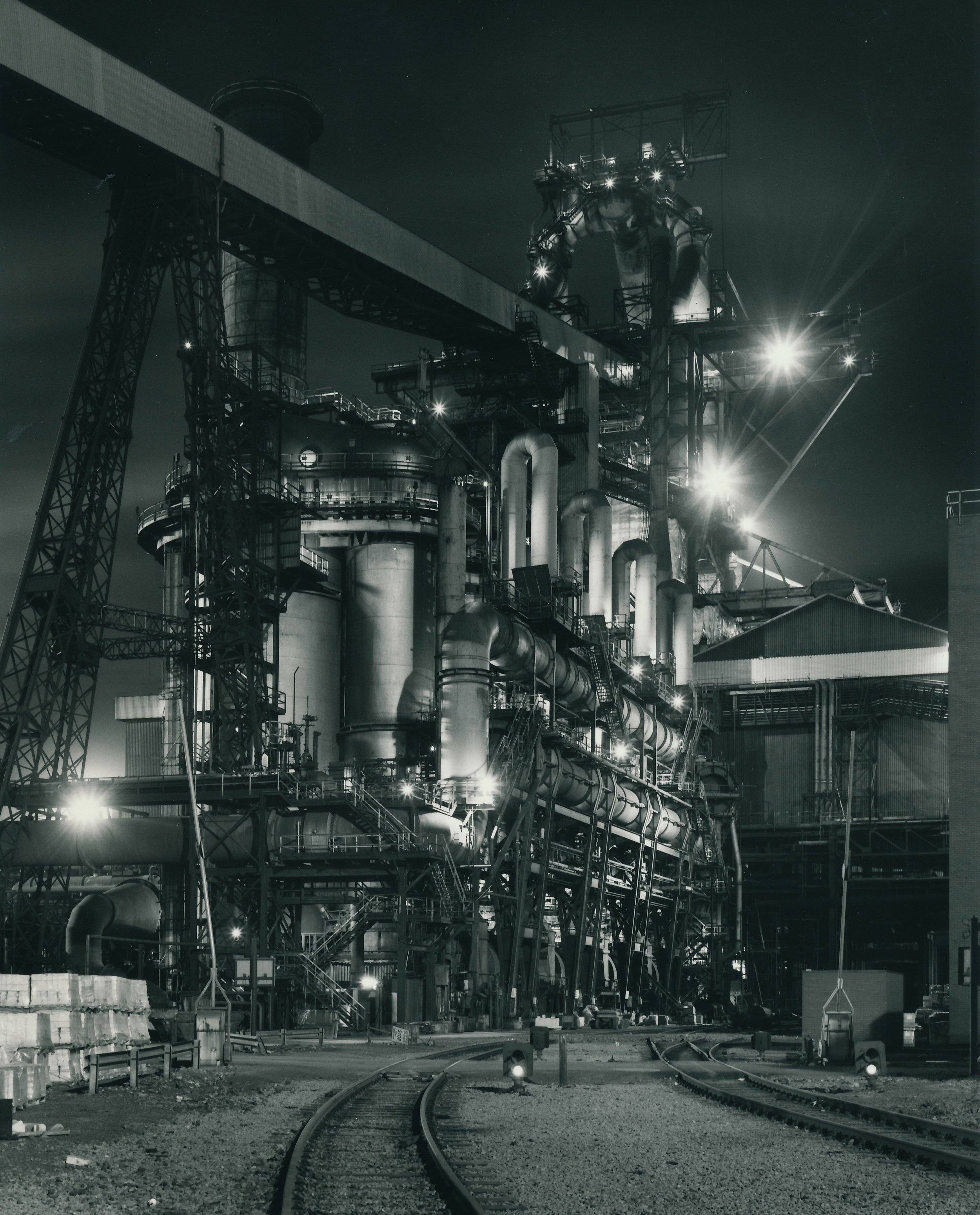

For us at the gallery, one of your most defining images is the Redcar Blast Furnace around 2 AM, midsummers night, which has a Dutch connection as well, as it was owned by a Dutch company, called Koninklijke Hoogovens.

Can you share the story behind this photograph? What was the experience like capturing and developing this image?

I first photographed in blast furnaces in 1972. Through the autumn of 1983 I worked in Redcar No.1 blast furnace for five months. I did feel I belonged there until early in January 1984 I was going back onto the furnace front side following the Christmas shutdown when I was asked who I was … more to the point I responded, “Who are you? For I have never seen you before!”. He was the new plant manager in charge of iron production, the big boss… He was also health and safety conscious and saw me as a threat to production, I would get in the way and it was just not safe for me. My pleas about the fact I’d being going in and out for five months without serious incident but more importantly that iron production was in the cultural DNA of Teesside, our heritage, which needed responding too, held no sway and I was barred. So in 1986, when the furnace was having it’s first major reline, I put the cultural angle to the company, backed up by sympathetic local councillors. I was granted limited access to photograph around the site accompanied, at all times, by a security guard and on no account was I allowed to make photographs inside the furnace.

I love to photograph at night and am especially drawn to significant nights, midsummer most of all. The guard and I wandered from dusk to dawn. We approached the furnace from the south, illuminated as it was by multiple lights and I became very excited. I seem to remember making two exposures of which the one you talk of was by far the best. It seems succinctly to sum up in one exposure the power of this mighty structure.

Redcar Blast Furnace around 2 AM, midsummers night, 1986

Your photographic oeuvre captures the essence of places and the people within them, highlighting their interconnectedness.

How do you approach conveying this relationship in your work, and what do you hope viewers take away regarding the interplay between people and their environment?

The interplay between people and the environments they find themselves in is crucial to most of the photographs I make. That we exist in space with things always around us is what offers a richness to our existence. Looking for my significances in how things relate one to another is what powers the structure of the images I make. I am hyper particular about how I go about framing the interplay of life and objects. I am frankly lost for words to describe the vitality of how we all exist with the things around us. Trying to fix this vitality down drives me forever onward.

Three cobles, traditional fishing craft in Greatham Creek Teesmouth, 1973

Special thanks to Ian Macdonald, for sharing his incredible insights with us throughout the interview!

All photographs in this exhibition are available to purchase. Please contact Elliott Gallery for further information.

Canteen staff at the end of their day, 1983

Ian Macdonald’s retrospective exhibition that is on view at Sunderland Museum & Winter Gardens until 4th January 2025 and was open at the Northern Gallery for Contemporary Art (NGCA) until 3rd November 2024.